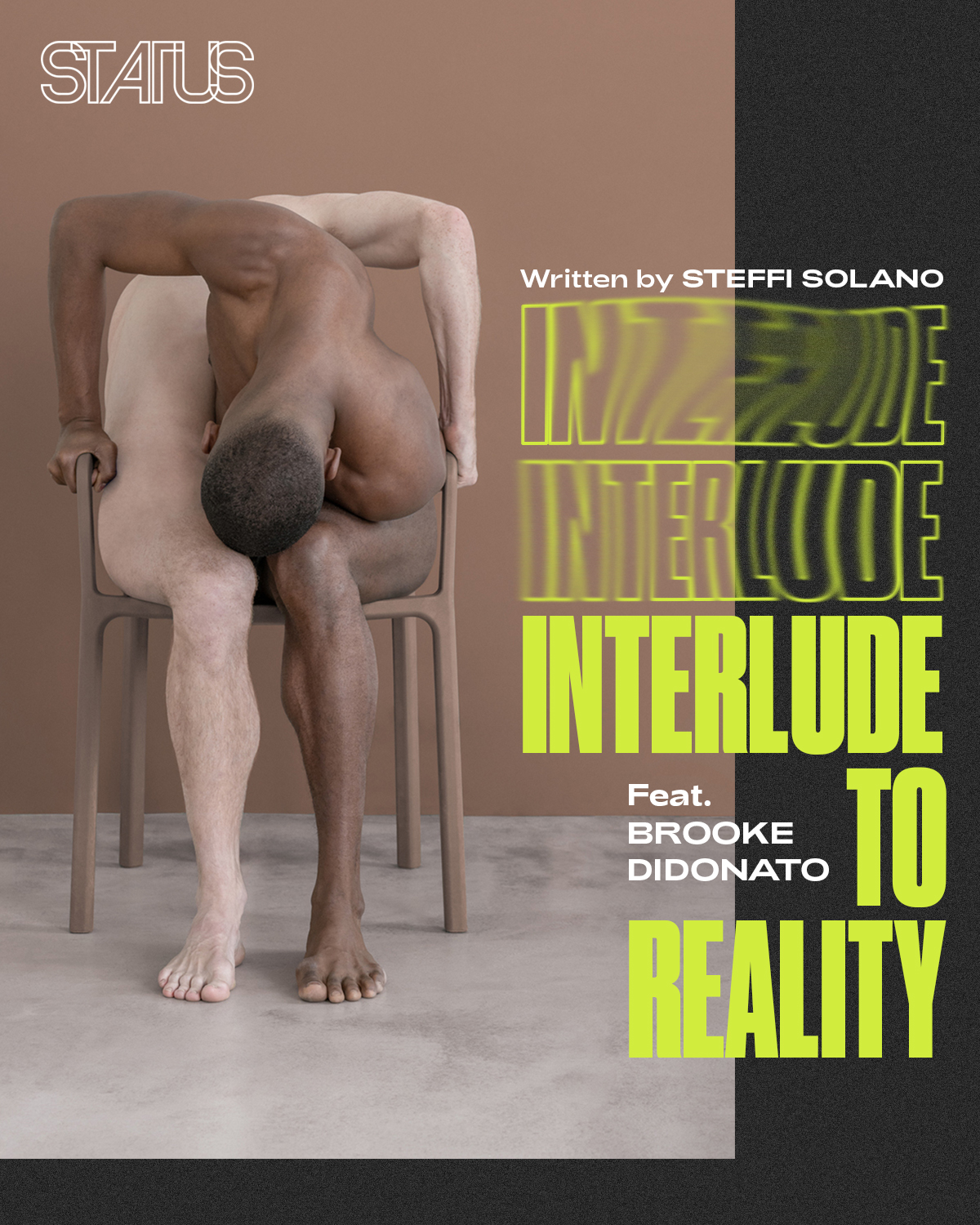

Surrealist Photographer Brooke DiDonato is Blurring the Lines of Reality and Fiction

Brooklyn-based photographer BROOKE DIDONATO has a penchant for the extraordinary. Her illusory visuals take image-making to another world; transporting viewers into her own Freudian universe in the process. She takes us on a step inside the trance and revel in the reverie of her art.

Her affinity for creativity rooted from a young age, possessing a fondness for art as she dabbled in drawing and painting and eventually established the dream to become an illustrator. Brooke’s desire to be an artist was what kept her going in the ambitious pursuit, despite her parents’ skepticism. “I told my parents at a very young age that I wanted to be an artist and I think it scared them. Then when I got older and had bills to pay, it scared me too,” she shares, but ultimately powered through that it was worth the chase. “The backbone of it comes from maintaining the mild delusion that everything will work out even when it doesn't. The desire was always there but it's more about putting all the fear on the back burner and saying ‘What am I going to make today?’ then going out and making that thing, even if no one is paying you to do it.”

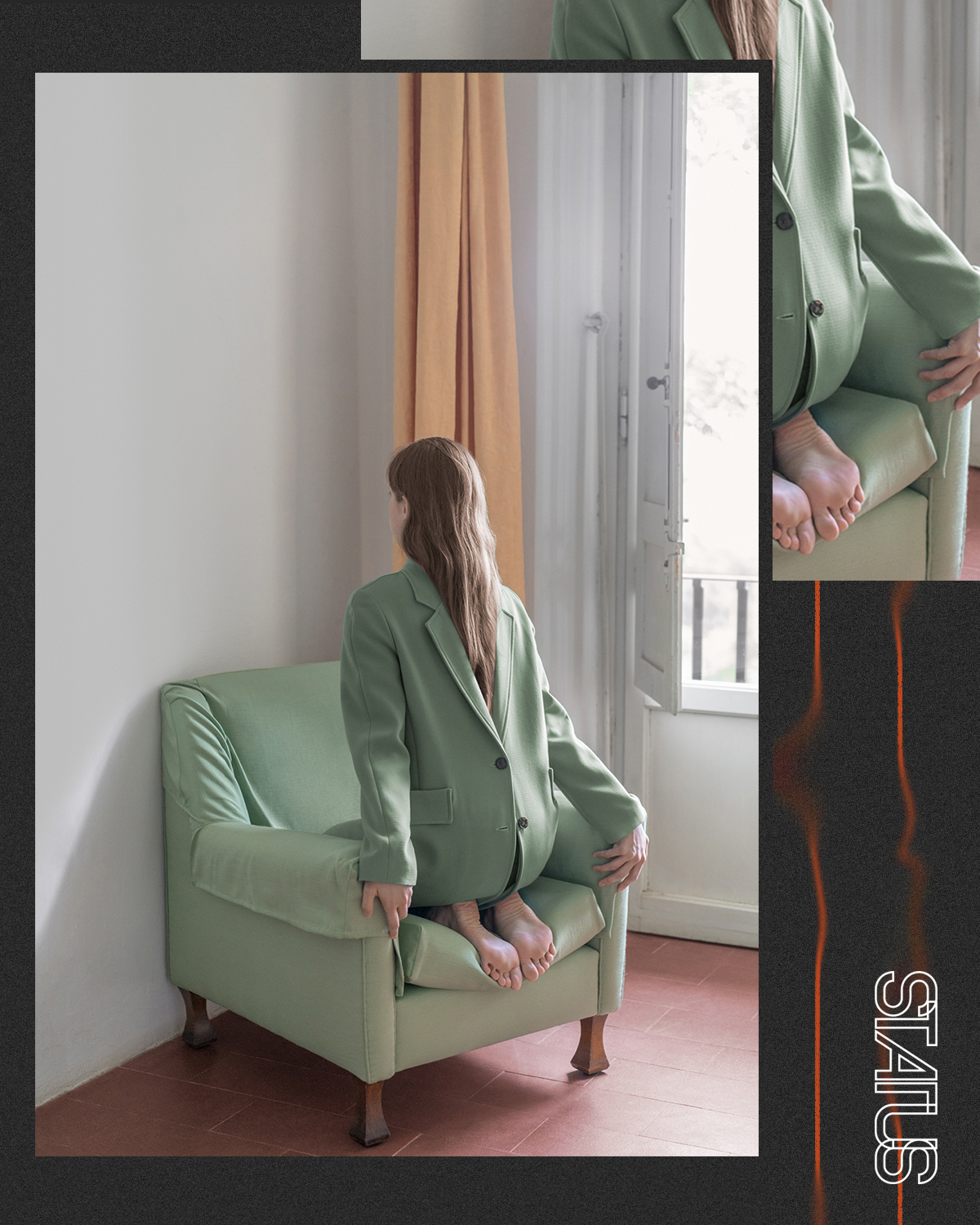

The illustrator goal bubbled down when she began experimenting with mixed media, sooner realizing the endless possibilities with using a camera alone; thus, taking the photojournalism route in university and started shooting self-portraits that she shared online. Brooke sought a challenge—moving to New York from midwestern Ohio working as an assistant to a photographer and consequently progressed to producing her own work. Despite moving to the East Coast, her roots of fascinatingly humdrum small-town Ohio became her very influence—dark suburbia presented in such a pretty, colorful way, flowers included. “I always thought I needed to move to a major city to make interesting work, but as it turns out, the backdrops of my childhood home became the foundation for one of my first self-portrait projects after moving there,” tells Brooke, referring to A House Is Not a Home, a series of images that tell of isolation and discontent from one’s home; the safety net of shelter broken through.

The approach became Brooke’s signature, with succeeding projects featuring mundane everyday Western scenes with faceless individuals, submerged bodies, dripping flowers, and botanical wallpaper. This originates from her Freudian fascination of deciphering and unfolding elements of the human psyche through imagery and the sheer idea of photography capturing something that can never be replicated, just like people’s psychological experiences. She calls the act of taking a photo itself surreal; how one can take an image knitted from one’s point of view and have it exist as a sole object. In a Brooke DiDonato image, viewers are placed in a narrative and evoke a sense of curiosity, sometimes an eeriness in its display. The images themselves automatically play out in your head and one might even find that they can make characters out of the people involved. The most compelling facet to Brooke’s creations is how it can bring in a myriad of feelings to the spectator but wrapped in an air of unfamiliarity, befogging reality and fiction’s borders.

Leaving the fantastical world of her art for a while, Brooke steps out to speak to us on the realities of being a creative, New York as a significant inspiration, and her favorite suburban element—floral wallpaper.

You grew up in Ohio and are now based in New York, did the stark difference between the two states influence your art process? If so, how?

New York made me see and appreciate Ohio in new ways. In terms of process, New York forced me into working more spontaneously and I think ultimately led me to create more site-specific photographs, like my recent work from the series As Usual. The pace is so much faster here and something interesting you see could very well be gone tomorrow, so instead of planning everything out like before, it was more like ‘Find something interesting? Go, go, go!’

You mentioned that you moved to the East Coast “in search of a challenge,” were you able to find this in New York? What were some obstacles you encountered?

Oh yes, plenty of challenges. Logistic challenges like how to share one bathroom with five roommates, how to carry six bags of camera equipment to the train and leave one hand free to swipe my Metrocard, how to stretch $50 for two weeks ($1 pizza slices are a blessing), how to sprint to meetings and not appear out of breath upon arrival. Creatively, I learned to work harder and stay humble. New York is a place filled to the brim with talent so there's not a lot of room for your ego. Listening more and speaking less helped too.

Your work features a lot of wallpaper. What are some of your favorite patterns? Is there a specific kind that speaks to your photography?

I really enjoy vintage floral patterns. I've actually been looking for a fabric to use for a project and I'm having trouble because the vibe is all wrong—modern trying to look vintage. The color palettes in patterns from the ‘40s and ‘50s are just so good, it's clearly not easy to replicate.

Did you have any artistic influences growing up? And what motivates you to do art today?

My only memory of being in an art museum before moving to New York was around age 17 when my art class took a field trip to the Cleveland Museum of Art. I remember seeing Andy Warhol's piece Marilyn x 100, and when we were back in class later, I googled his name and found all of these famous quotes. Since then, I've always admired his candor—the way he spoke about life and art in a way that even 17-year-old me could understand; it's accessible.

What has been the most challenging project you ever took on?

The most challenging was definitely my 365 project I did back in 2011. My goal was one conceptual photo per day for a year but I had no real theme or artistic guidelines for myself so I feel like I really just floundered through the whole thing never knowing what I was doing. The end result was about 10 decent pictures from an entire year of work but I still think very fondly of that time because I was able to experiment so freely.

How can you say that a work is done, that this is ‘it’? From the perspective of a creative all-rounder, what makes a good artwork?

I'm not always good at knowing when my work is done. When I'm unsure, I make multiple versions and overwhelm my partner with every scenario in my mind for the toning, composition and crop. Then from there, it's a gradual pairing down until she refuses to humor me any longer. It's a luxury to have an editor that you trust. Good art is subjective, but if it affects you in emotion, aesthetic, or function, it's probably halfway there. If it does more than one, all the better.

In your opinion, do photographers take photographs or do they make them?

I think photographers are capable of doing either. If your presence altered the scene, you probably made the picture. Patience makes pictures too.

What’s a piece of advice you could give to young artists who want to pursue a career in photography?

Experiment, make mistakes, repeat experiments without mistakes. Always keep a personal project in the works. Learn everything you can about business.

How do you see your style evolving in years to come?

I would like to make more installation work—take my photographs out of the 2D realm and move them into elaborately staged scenes that people can enter and interact with.

Post a comment